Hoe onze hersenen context gebruiken/en: verschil tussen versies

Nieuwe pagina aangemaakt met '== Example: a crying boy ==' |

Nieuwe pagina aangemaakt met '== Illusies als venster op context ==' |

||

| (Een tussenliggende versie door dezelfde gebruiker niet weergegeven) | |||

| Regel 69: | Regel 69: | ||

== From perception to behavior == | == From perception to behavior == | ||

The way our brains use context not only determines what we see or hear, but also how we react. | |||

If the context tells us that a sound is dangerous, we will be startled. | |||

If the context is reassuring, we may interpret the same sound as harmless. | |||

< | <span id="Verder"></span> | ||

== | == Further == | ||

See also [[Special:MyLanguage/What is context?|What is context?]] for a general introduction, and [[Special:MyLanguage/The spectrum of context sensitivity|The spectrum of context sensitivity]] for the differences between individuals. | |||

Huidige versie van 22 sep 2025 15:26

The brain as a prediction machine

Our brains do not passively absorb reality. They actively work as a prediction machine. Every perception is the result of a continuous comparison between:

- the sensory input that comes in

- the expectations our brain has built up beforehand

This principle is described by Karl Friston as the Free Energy Principle (2010): brains constantly try to make the "error" between expectation and reality as small as possible.

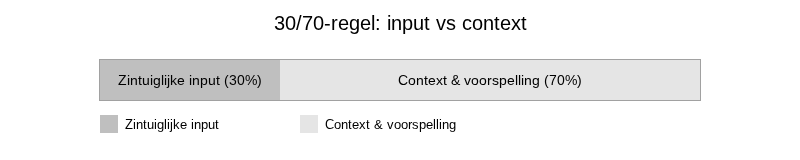

The 30/70 rule

Researchers estimate that our experience of reality consists of only a limited part of "raw input." Approximately 30% of what we perceive comes directly from the senses, and 70% is supplemented by our brain through context, memories, and expectations. Context therefore determines the largest part of our experience.

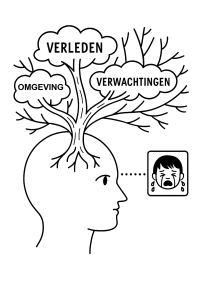

Example: a crying boy

Imagine you see a boy crying. The first, primary reaction is: to comfort him. But context can completely change the interpretation:

- The child cries frequently → you decide not to constantly comfort him, because he needs to learn that falling is not always bad.

- The mother is present → you feel that your intervention is not necessary.

- The child is crying with joy → his team has just won a soccer match.

- The mother is present, but reacts coldly and uninterested → how do you handle this without getting into a conflict yourself?

The same behavior can therefore lead to completely different reactions, depending on the context.

Individual differences in context processing

That context determines interpretation is understood by almost everyone. What is often less recognized: the context sensitivity itself also differs among people.

- The past and experiences of each person are different.

- But in addition, the ability to process context - what I call complex thinking - is also developed differently.

Some people are good at it, others have more difficulty. This means that the same situation can be understood or handled very differently by different people.

Selection and filtering

Context also helps us not to get overwhelmed with information. Of the thousands of stimuli that come at us per second, only a fraction reaches our consciousness. The rest is automatically filtered:

- background sounds disappear to the margin

- irrelevant visual details are suppressed

- emotionally important signals are actually amplified

Illusies als venster op context

Visual and cognitive illusions show how strongly context colors our thinking. The brain makes assumptions based on probability, and sometimes ignores the “raw data.” This is how we understand why:

- a shadow makes an object appear darker or lighter

- an unexpected event (such as the gorilla in the Monkey Business Illusion) can be completely ignored

From perception to behavior

The way our brains use context not only determines what we see or hear, but also how we react. If the context tells us that a sound is dangerous, we will be startled. If the context is reassuring, we may interpret the same sound as harmless.

Further

See also What is context? for a general introduction, and The spectrum of context sensitivity for the differences between individuals.